Can marketing help us being vegetarian?

A societal study identifying meat consumption patterns

Climate change is no longer some far-off problem; it is happening here, it is happening now. – Barack Obama

…affecting our planet and our society. Hence, it is time to take the relevant steps to avoid the worst impacts of it. This concerns various dimensions, such as renewable energy, emissions and agriculture. Most importantly however is to note, that each of us is able to fight climate change. It starts off with a very simple issue: our food consumption. Dietary changes towards healthier diets can help to reduce the environmental impacts of the food system, in particular with regard to animal products, when they are replaced by less intensive food types [Nature]. This form of human diet can actively promote a change in the amount of greenhouse-gas emissions [Nature 572, 291-292 (2019)].

Since this project’s overall goal is “Data Science for the good”, an analysis of our daily consumption of everyday commodity products taken from Household Transactional Data offers the potential to reveal patterns and latent structures and relations in the interaction of marketing and transaction behavior on meat and vegetarian products. With transactions from more than 2500 households from different societal status over 2 years the data set “Dunnhumby - The complete journey”, used in this analysis, offers the chance to link societal status, income and living constellations to a topic which gains more and more importance our meat consumption.

Knowledge about interdependencies and drivers of customer preferences and behaviors is a crucial factor for effective customer-based strategies. Having these insights at hand, it might be possible to develop new strategies to actively take influence on improving awareness for meat consumption via more precisely targeted advertisements and promotions, satisfying both the customer himself, as well as the retail industry. For instance, a correlation of households with lower income households exhibiting a less balanced/more meat-focused food could be dispersed by placing well-suited advertisements for more vegetarian food.

Demographic landscape of the households in the data set

This data set contains 2500 households who are frequent shoppers at a retailer. It contains all of each household’s purchases from a diverse number of categories (not only food-related). For certain households (801 out of 2500), also demographic information, as well as direct marketing contact history was included. This covers at least one third of the population to gain an overview of the demographic landscape of the corresponding data set.

First looking at the age ranges, the biggest share (~35%) of households covers a range of 45-54 years, followed by a range of 35-44 (~25%). The smallest share is represented by the 19-24 years range, corresponding in most cases to Single Households. It can be further inferred that most of the 801 households are married or at least in partnership, which split up in nearly equally sized subgroups of having children and not having children. The third group in the marital categorization is includes Single households. It includes households from all age ranges.

Further the demographic description provides insight in the financial situation of the households, covering a range from households earning below $15K up to $250K+, whereas the biggest group is represented by the households earning 50 to $64K, which is a roughly reasonable estimate of the “real” population.

Consumption Behavior

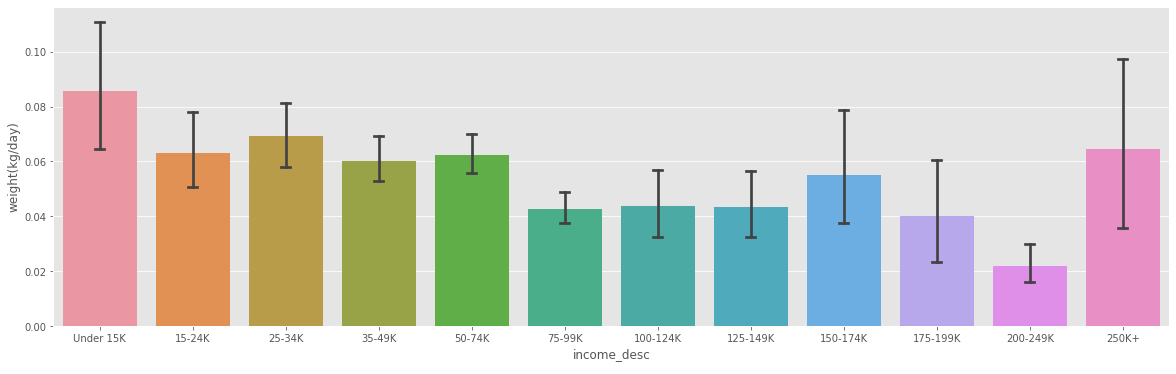

Are there differences in the meat consumption between groups with different incomes? Do people with a higher income eat more or less meat? To find out, we calculate the daily weight of meat bought by each household (normalized by the number of people in the household).

Let’s look at a plot of the different income groups we have. To be able to actually say anything about the data, we also plot the 95% confidence interval.

The graph reveals the following: Households with lower income (i.e. an income of less than 15K per year) tend to buy more meat that groups that earn between 75-149K. On the one hand, this might seem counter-intuitive in countries like Switzerland, since meat can be very expensive there. On the other hand, nowadays there exist many cheap meat products from factory farming, especially in countries like Germany or Austria. However, if we check with our data, we see that meat in fact is more expensive than the rest, with a median price of $3.50, versus $2.66 for food in general.

Another interesting observation is that the lowest meat consumption comes from the second highest income group of 200-249K. The consumption is significantly lower than of the aforementioned income brackets. This provides ground for the assumption that there actually is an inverse relation between the household’s income and their meat consumption. However, this is still only a very weak assumption since the share of high-income families in the data set is very small and definitely not exhaustive for the bigger population. Also, regarding the fact that the household group earning $250K+ shares roughly the average meat consumption with the other groups. Further, the household composition of these groups is not equally distributed, meaning the $200-$249K group does not incorporate any singles and the $250K group is dominated by adults without kids. Albeit the above limitations, this assumption could also imply that households and especially families with higher incomes are potentially more conscious about their food choices, buying for example fewer, but higher quality meat and more vegetables.

Going further, meat consumption is way less clear for the different age categories. In fact we can’t say there is any significant difference between the age groups after running ANOVA and other statistical tests. However, we will still show it below for the interested reader.

We can also look at the households meat consumption by splitting them according to their age, but in that cases there do not seem to be any significant differences.

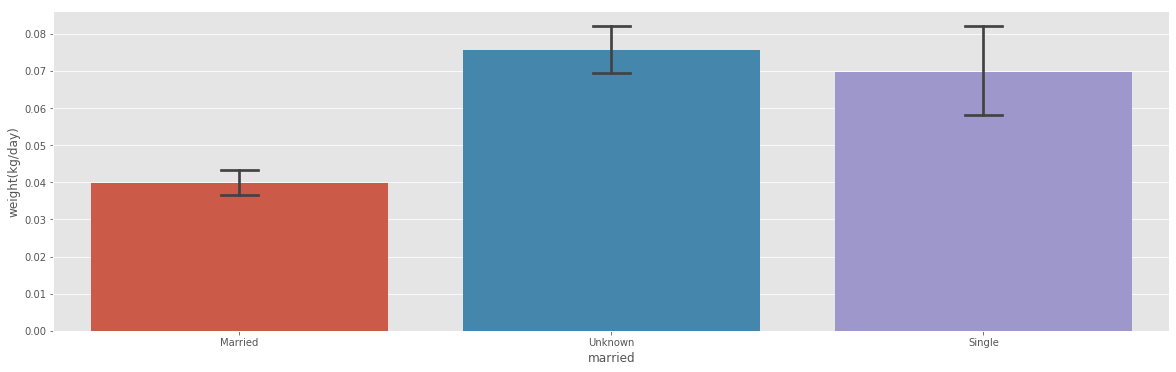

In order to find out if the differences we have seen are statistically significant, we have run a Kruskall-Wallis test for the three case studies (households splitted acccording to their income, their age and their composition). As expected, the differences among groups of different age are not significant (statistic H=10.4, p-value=0.066 > 0.05) but they are for the income (statistic H=32.2, p-value=0.00072 < 0.05) and for the household composition (statistic H=133.8, p-value=9.02e-30 < 0.05). Indeed, we have the following significant results:

- single people buy more meat than people with no kids (p-value=0.001)

- single people buy more meat than people with kids (dp-value=0.001)

- people with no kids buy more meat than the adults with kids (p-value=0.0202)

- the Under 15K group buys more meat than the 100-124K group (p-value=0.0178)

- the Under 15K group buys more meat than the 125-149K group (p-value=0.0103)

- the Under 15K group buys more meat than the 75-99K group (p-value=0.001)

Finally, we look at household with different compositions. This time the differences seem to be significant. Indeed, single people buy a lot more meat than households with multiple people (either with or without kids). This might be due to healthier food choices made when cooking a meal for an entire family. We all know how we tend to eat lower-quality food when leaving alone. It is also interesting to notice that people with kids are actually the ones buying the less meat. This might be due to the different dietaries children have to follow in order to grow well.

However, if we regroup the existing data we have about adults without kids and kids vs singles, we can still see some amusing differences.

Which categories of food are being promoted during campaigns?

The Role of Coupons

Marketing plays a big role in people’s grocery shopping behaviour. Are people directed to buy meat and fish? To take a look at that we observe two marketing aspects: the discount coupons distributed during promotional campaigns and advertisement.

We first look at the coupons distributed during the 30 campaigns. To get a vague idea of the campaigns, we look at how many coupons they distribute and at how many coupons are actually redeemed. It is important to consider both the distributed and the redeemed coupons as we want to not only consider the marketing choices but also how people respond to them.

We can see that the coupons do have an impact, since many of them actually get redeemed. In fact, around 86% of distributed coupons are getting redeemed. This means coupons (and promotional campaigns in general) do have a way to influence people consumption behaviours: if many coupons are distributed for specific products and people tend to redeem them, the sales of those specific products will go up.

With that in mind, let’s take a closer look at the coupons and which food categories are promoted. We display the proportions of coupons distributed in the ten categories of food previously designed. Note that the remaining parts of distributed coupons are for non-food products.

Feel free to explore what kind of food items are being promoted by the campaigns. When you’re ready, continue on to find out what part meat and seafood (the non-vegetarian products) play in the campaigns.

Promotions for Meat and Seafood

Let’s have a look at the proportions of coupons distributed for vegetarian and non-vegetarian products.

We can see that the campaign individual shares of meat or seafood related coupons are mostly low. Only in 5 campaigns out of 30 the proportion of coupons distributed for non-vegetarian products is higher (campaigns 8, 13, 17, 18 and 23). It seems that campaigns tend to promote more vegetarian products, but do we have the same picture from the people point of view? Let’s have a look at the proportions of coupons redeemed by the households to answer this. Here again, we have grouped products into two categories: vegetarian and non-vegetarian.

As expected, since we already know that most coupons are redeemed, the picture here is very much the same. People tend to use more coupons for vegetarian than for non-vegetarian products.

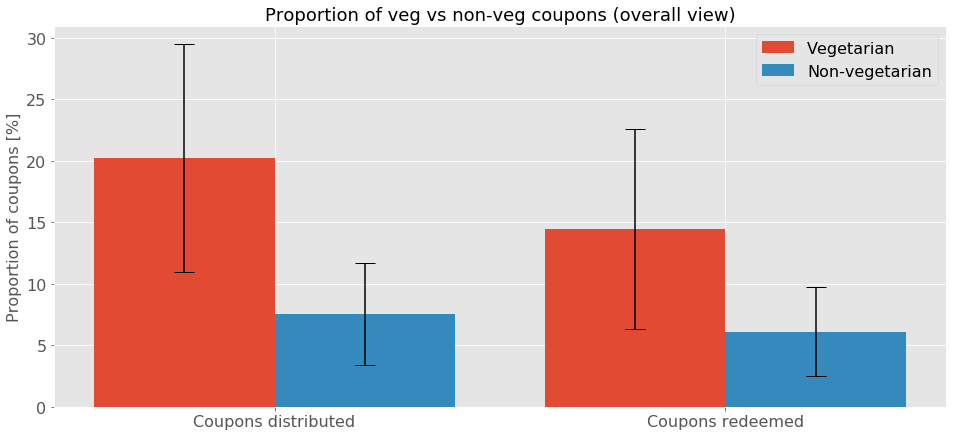

Let’s try to summarize these observations by having a more general view, looking at the average proportion of coupons distributed and redeemed for vegetarian and non-vegetarian products, across all the campaigns. We display those means with the corresponding errors at 95% confidence level.

Since the errorbars seem to overlap (at least for the coupons redeemed) we run additional statistical tests to find out if the differences observed are significant. The proportions of coupons are the following:

- coupons distributed: 20.2 ± 9.24 % (veg) vs 7.55 ± 4.16 % (non-veg)

- coupons redeemed: 14.4 ± 8.12 % (veg) vs 6.11 ± 3.63 % (non-veg)

Since the assumptions of normality and equality of variances are not met by the two groups of coupons, we have run the Mann-Whitneyu’s test to find out if the differences are indeed significant. The results are conclusive for the coupons distributed (U=297, p-value=0.0117 < 0.05), meaning there is a significant difference in the proportion of coupons distributed for vegetarian and for non-vegetarian products. Unfortunately this is not the case for the coupons redeemed (U=370, p-value=0.1162 > 0.05), meaning that the proportions in the two categories could in fact be similar.

Next, we look at the other marketing aspect: advertisement. Coupons are only half the story when the influence of the campaigns is concerned. The campaigns also distribute leaflets advertising different items. These ads can be in different parts of the leaflet. So how are the different food categories advertised?

The best position in a magazine is certainly the front page. Approximately 15% of all meat and only 1% of the fish products are advertised on the front page. On the other hand, vegetarian animal product are in 30% of the time are displayed on the front page. The numbers for vegetables and fruits are 10% and 7% respectively. Again, it does not appear that meat or fish is particularly advertised.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we can say that it seems like marketing does not promote meat and fish consumption, but instead does so for vegetarian products, meaning that there is still hope for our planet! :-)

In Love,

Your dADA-Scientists